An Arbor Month Tree Trilogy

By Anna Barker

“What’s your favorite tree?”

“Oh I don’t know, maybe a white pine.”

“Mine’s definitely apple trees because you can eat them.”

“No you can’t, Silly, laughing, nobody eats trees!”

“You know what I mean!”

“Don’t be so literal all the time.”

“OK, OK, I was just joking around.”

“I know; no problem. We better hurry up – look how far ahead everybody is!”

Voices from the past float back to the present and I am reminded how much I miss being a teacher, especially in the spring time.

May is Arbor Month in Minnesota. And when I was at Crosswinds Arts and Science School in 2005, we celebrated all of the work required by the DNR to have our seventeen acre site certified as an urban School Forest. Located on the edge of Battle Creek Lake across Highway 94, there is 3M, a corporate reminder of how global citizens get transplanted to our Twin Cities metropolitan area and how our lakes and the Mighty Mississippi and trees tie us together as human beings – we all have favorites and have the need to “catch up with others” and be seen, heard, listened to, and have fun!

In spite of how we share and have in common our love of trees and water, I think too many Minnesotans take their lakes and rivers and creeks and trees for granted. We are blessed and lucky to have all our blue and green so close to us in our daily lives and should be grateful partners with Mother Nature in their care and stewardship.

However, we are seeing the effects of climate disruption, caused in large part by human greed and short-term thinking. Our biomes here in Minnesota and globally are beginning to change, and our water quality is being challenged. At this point in time, it is critical for our lakes, rivers, creeks, streams and trees that we do all we can to take care of them the way they take care of us. Let us count the ways that we can make a positive difference for them and for ourselves every day of our lives. Choose what your favorites might be and then – you know the slogan, “Just do it!”

| Water Action Day at the Minnesota Capitol |

Below are listed the forty organizations who were involved in Water Action Day that I attended at the Capitol on April 20. You can visit their websites and get ideas about what people of all ages can choose from and do to get engaged in protecting our water.

|

| Friends of the Mississippi River, one of forty organizations involved in Water Action Day at the Minnesota Capitol. |

These organizations participated in the Water Action Day

Mississippi, Anglers for Habitat, Audubon Minnesota, Clean Water Action, Coalition for a Clean Minnesota River, CURE, Duluth for Clean Water, Fish and Wildlife Legislative Alliance, Friends of Pool 2, Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness, Friends of the Mississippi River, Honor the Earth, Izaak Walton League, Land Stewardship Project, League of Women Voters, Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, Minnesota Environmental Partnership, MN350, MN Interfaith Power and Light, MN River Congress, New Ulm Area Sports Fishermen, Save Our Sky Blue Waters, Save the Boundary Waters, Sierra Club North Star Chapter, St. Croix River Association, Sunnyside Marina (St. Croix River), WaterLegacy, Alliance for Sustainability, Bob Mitchell’s Fly Shop, Conservation Minnesota, Cool Planet MN, Duluth for Clean Water, Environment Minnesota, Fly Fishing Women of Minnesota, Friends of the Headwaters, Great Old Broads for Wilderness, Minnesota Trout Unlimited, MN Conservation Federation, Native Lives Matter, Powershift Network, and Voyageurs National

Park Association.

Get Your Daily Dose – Hug a Tree

|

| Barb Spears and Terri Heyer, passionate supporters of trees

Photo credit: Cleanwatermn.org

|

Barb Spears and Terri Heyer have a life-long passion for trees. Terri is an Urban Connections Program Specialist for the US Forest Service. Barb serves on the board of the MN Shade Tree Advisory Committee, is a volunteer with the St. Paul Tree Advisory Panel and is an avid leader in the Minnesota Women’s Woodland Network.

For a glimpse of their perspectives on trees, peruse this article in cleanwatermn.org called Tree Huggers Unite: Protecting Urban Tree Canopies. Both these women cite Dutch elm disease, which ravaged urban forests in the 1970s, as an early inspiration for their dedication to the kinds of work they do.

As they both acknowledge, trees have many values from stormwater interception, climate control, improving air quality to providing a variety of social and health benefits.

The Arbor Day Foundation states that a tree, depending on its size and species may store 100 or more gallons of water after one to two inches of rainfall. The top of the tree act acts like an umbrella where leaves and bark break the impact of a rain event and absorb water. The roots both take up water and bind soil preventing erosion. Part of this intercepted water will evaporate and part will be gradually released into the soil below.

At the surface of the soil, fallen tree leaves help form a spongy layer that moderates soil temperature, helps retain soil moisture, and harbors organisms that break down organic matter and recycle elements for use in plant growth. This important layer also allows rainwater to percolate into the soil rather than rushing off carrying with it soil, oil, phosphorus and other pollutants. Below ground, roots hold the soil in place and absorb water that will eventually be released into the atmosphere by transpiration.

Spears and Heyer see roles for every resident in tree care and maintenance. “It has to start outside your back door,” says Heyer. “Every tree counts.”

|

|

Photo Credit: Cleanwatermn.org

|

To tap into the roots of several other tree-passionate individuals, you can tune into these fun video vignettes on the DNR website with stories by Alex Van Loh and Shanti Penpraise from Freshwater Society.

|

|

Photo Credit: Minnesota DNR

|

What’s a good way to show your own love for trees? Take the #31 Days of Trees Challenge that the Minnesota DNR is promoting during Arbor Month in May.

|

Photo Credit: Minnesota DNR

|

Simply post a photo or video of you enjoying your daily dose of trees on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram (or all three!) along with the #31DaysOfTrees and include @MinnesotaDNR when posting to Facebook. Participation will be tracked using #31DayOfTrees. You may win one of five State Parks permits and have ten trees planted in your honor at one of our Minnesota State Forests. The more times you post enjoying your daily dose of trees, the more chances you have to win!

Enjoy your daily dose of trees!

——————————————–

By Sage Passi

|

| Burr oaks on the Dakota Trail |

In early April, on one of the intermittent, spring-like days we’ve been having lately, my friend Steve Simmons, a retired U of M agronomy professor and I decided to embark on a hike on an old Indian trail. He had often talked about the old compass tree he would pass by on his way to the St. Paul campus. This area was also my old stomping grounds in years past. I had driven up Raymond Avenue from its intersection with Cleveland Avenue in St. Anthony Park hundreds of times on my way to the food co-op I managed for years, but I never knew about the trail or the tree.

|

| The compass tree. |

A month or so before this, I was on a quest to find out about the history of two lakes that I would be taking Central Park Elementary students to in the spring – Lake Owasso and Lake McCarrons. This led me to look more closely at the history of Roseville and Shoreview and their land changes. The north line of the old Rose township, the precursor community to Roseville touches Lake Owasso. When I researched its name I came up with two possibilities.

Owasso is an Osage name meaning “the end” or “turn around”. The Roseville Historical Society produced another explanation for this name, citing a reference to the Ojibwe word, “Owaissa” from Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha which means blue bird. This would have more resonance and significance to me later when I learned about Tallamy’s research on native trees and caterpillars. If you dig deeper into the Song of Hiawatha and the word, “Owaissa” you can find references to the historical tensions between the European settlers and Indian tribes embedded into the story line of the poetry.

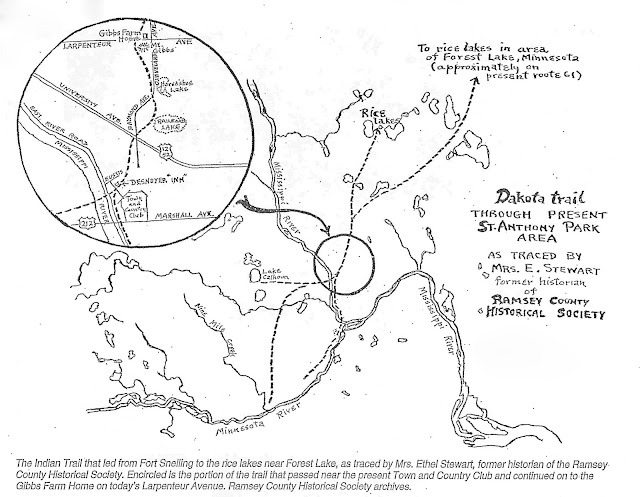

Coincidentally, around the same time while assisting students at Farnsworth with some seed starting, a Master Gardener named Katja Hernandez and I had chatted about my interest in the history of Roseville, a city where she resides. She told me she works at Gibb’s Farm and that she had a map of an old Indian trail that intersected this area. I said that I had recently discovered that Cleveland Avenue starting near the Mississippi River follows the route the Dakota took to lakes further north where they harvested wild rice.

On her prompting I began reading about Cloud Man’s village by Bde Maka Ska (Lake Calhoun in Minneapolis) and learned about his tribe’s and family’s “migrations” along what is now called Lake Street, then across the river and up along this route to the north. I was fascinated to learn more about this Dakota chief, Maḣpiya Wic̣aṡṭa, since I have lived near the Mississippi River on the Minneapolis side, close to this crossing area for years and have studied Dakota history and culture since my childhood. Every day I pass by the Town and Country Golf Course which marks the start of this trail’s traversing to the north on the other side of the river.

|

|

1860 Sioux Camp

Photo credit Minnesota Historical Society |

|

| Did the oak trees point the way for the Dakota to find wild rice? |

The Dakota constructed Cloud Man Village in a marshy area to the southeast of the lake where they previously harvested wild rice. They called it Heyate Otunwe, or “the village at the side” where they began farming to supplement their food supplies that were dwindling because of losing areas of hunting and fishing territories through treaties in the early 1800’s and conflicts with other tribes.

The Dakota at Heyate Otunwe had always gardened and harvested food from wild and native plants, but the concept of large-scale farming and living off plants that were not indigenous to the area was something new to them.

I knew that the Dakota paddled up lakes in our watershed, but I pondered whether or not there was wild rice growing in any of these shallow waterways and if they ever harvested it.

Equipped with a close-up of this map of this Dakota trail provided by Katja, Steve and I set off on our journey on foot up Raymond Avenue. Steve’s passion for burr oaks was evident as he scanned the hills for remnant oaks from this earlier time period. We stopped in the park to speculate on the ages of these majestic burr oaks perched on this knoll with their sweeping arms embracing each other.

As we continued traveling up Raymond Avenue, we paused to peer into fenced yards situated along this old trail route. What we found were definitely some really “old” oaks judging from the size of them.

|

| Was this burr oak around in the early 1800’s? |

These trees were definitely some of the largest burr oaks I’d seen and probably some of the oldest. Burr oak’s massive trunks can support heavy, horizontal limbs and can exceed 100 feet in height. They have rough, deep-ridged bark.

|

| Doug Tallamy, University of Delaware entomologist and author of Bringing Nature Home Photo credit: Douglas Tallamy, Wild Ones

|

According to Douglas Tallamy, a University of Delaware entomologist and author of the book, Bringing Nature Home, an oak can host up to 553 caterpillars including 19 species. I listened to his keynote speech at this winter’s Wild Ones Conference. He expounded on the value of native trees over exotic species brought over from other countries that don’t provide adequate nutrition because they haven’t evolved or functioned within the web of their native wildlife and insect counterparts.

|

|

Bluebird with caterpillar

Photo credit: Doug Tallamy

|

I was glad to see these oaks were still growing in the neighborhood and not replaced with more “urban” trees like gingkos and other non-native species that don’t provide the ecological services that these native species offer wildlife. By comparison, a gingko, according to Tallamy’s research, can provide only up to four caterpillars for a hungry bird family. These burr oaks, by contrast, are virtually a healthy breakfast, lunch and dinner café for birds that feed their hungry broods in a steady rush from 6 AM to 8 PM.

As we got to where the trail disappeared behind houses on the northern end, Steve and I stopped to admire two especially mammoth oaks. Steve said he had the feeling they may have been young oaks when Cloud Man, his family and tribe or perhaps other Dakota traveled through this area. The compass tree, not far off the trail, had pointed the way to their sources of nourishment to the north.

|

| Burr oak’s massive trunks can support heavy, horizontal limbs and can exceed 100 feet in height. |