School Retrofits: Allowing the Flow to Happen

By Sage Passi

|

| What’s the area of our driveway in front of Central Park? These students took on this math challenge to determine the drainage area for their future rain garden. |

Things have a way of eventually coming together. Our efforts over the past four years have involved the search for schools that are open and willing to be models for stormwater retrofits in their community. We’ve identified teachers who like hands on learning. We’ve connected with partners who are interested in working with schools – Maplewood Nature Center, EMWREP and Ramsey County Master Gardeners. Master Water Stewards have been assisting us with our field activities to help students understand the elements built into rain gardens and how they function.

We’ve gotten acquainted with kids who are curious and open to trying new things.

|

| An auger is not something kids use every day! |

We’ve been equipping students with tools that help them understand the “whys” and “hows”.

|

| Woodbury fourth graders interpret a map of their school grounds to see where run-off comes from impervious surfaces and travels to their future rain garden site. |

Along the way we’ve been lucky to engage with scientists and teachers who have the desire to meet each other on the playing field.

As we close in on implementing the culminating steps of our state grant, “Engaging Schools in Retrofit BMPS”, the excitement has been building. It’s no longer just a vision. It’s concrete, it’s real and we are doing it!

Central Park Elementary, Roseville Area Middle School and Woodbury Elementary Schools are in the spotlight this year.

As summer moves along, retrofit rain gardens are being constructed on their school grounds. When I drove over to Central Park Elementary in Roseville one afternoon in late June, I saw the contractors wetting the concrete to cut the inlet for the new rain garden with a circular saw. I stopped to watch, mesmerized and in awe. This step, while just one small action in the process, was symbolic to me, representing the accomplishments of cutting through resistance, opening up to change, and allowing the flow to happen!

|

| Cutting the curb for the rain garden inlet at Central Park Elementary |

The construction of these rain gardens takes anywhere from a week to two weeks, depending on their size. The Central Park Elementary rain garden was able to secure “center stage”. As the buses entered the driveway in front of the school, they lined up next to it. We couldn’t ask for a better front row seat for students attending summer school to watch the construction unfold.

|

| Rain garden construction at Central Park Elementary in Roseville |

|

| As work continues, a limestone wall emerges that will frame the back of the rain garden. |

Bonding with Local Water Bodies

In preparation for the installation of these three rain gardens, we felt strongly that it was essential to connect our youth audience with the lakes and streams we are trying to protect. In early March Woodbury Elementary students traveled by bus to Battle Creek Lake to study its water quality. Roseville Area Middle School students came to our office site in late May to trace the flow of their stormwater to Gervais Creek that flows below our office windows and look at how our rain gardens function.

We set up two half-day field trips in early May for Central Park students to visit their downstream lake with time built in to explore, play and conduct research. The morning became a blend of structured and less structured opportunities to invite inquiry, wonder and foster curiosity.

|

| Central Park fifth graders explore Lake Owasso’s shoreline on their spring trip to learn about water quality in their watershed. |

|

| A baby snapping turtle appeared at the beach. |

We knew many of the students at Central Park Elementary were more familiar with nearby Lake McCarrons, so we decided to blend a field trip to both Lake Owasso and Lake McCarrons. This became an opportunity to illustrate the concept of watersheds by using maps before the trip to illustrate that water on the land has many paths to nearby lakes, but still ends up downstream in a larger watershed – The Mississippi River. We pointed out the watershed divide between Capitol Region and Ramsey-Washington Metro Watershed Districts and explained that while their school’s run-off ends up in Lake Owasso, if they live in other areas near the school, it flows to Lake McCarrons.

|

| Central Park Water Flow |

Team-Teaching Strengthens Our Approach

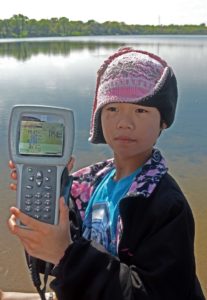

We invited our water quality intern to assist us on the field trip. Lyndsey Provos demonstrated the use of the monitoring equipment she uses on various lakes in the watershed. Prior to her position with RWMWD, she spent time in graduate school working on data collection on Lake McCarrons, so she was familiar with the conditions on that lake.

|

| Lyndsey Provos, the District’s water quality intern, introduces Central Park fifth graders to the Sonde which she used to help them collect data about Lake Owasso. |

|

| What water quality parameters can we measure with the Sonde? |

The RWMWD has assigned a water quality classification of “At Risk” to Lake Owasso based on recent water quality data at or near the MPCA and RWMWD nutrient water quality standards.

Jordan Wein, a fish specialist with Carp Solutions, met classes at Lake Owasso on both days to expand the story of water quality to include what is living in the lake. He is beginning a population study of carp in Lake Owasso and Bennett Lake. He brought some samples of equipment including a trap net and his radio tracking devices to show students the tools he is using in his research with the Watershed District.

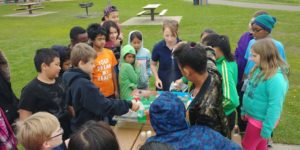

Teaming up with Lindsay Schwantes, Community Outreach Coordinator for Capitol Region Watershed, provided great support. She introduced a number of fun activities to the day’s mix including a game, ‘Sharks and Minnows’ that she adapted into an action packed exercise in the park next to Lake McCarrons. Students took on roles as sediment, hydrologists and rain gardens. Hydrologists tried to tag as many ‘Sediments’ as possible as they ran from one end line to the other. If students playing the roles of ‘Sediment’ were tagged, they became rain gardens who remained stationary but could still reach out to try to tag any ‘Sediments’ as they passed by.

|

| “1, 2, 3, RUNOFF!” |

Lindsay also engaged student in the use of the enviroscape to illustrate how run-off impacts downstream waters.

|

| Lindsay Schwantes introduces the fifth graders to the enviroscape. |

Classes walked around the perimeter of the lake, tracing its route through a storm drain, then underground, then flowing out into a marshy area adjacent to the beach before it heads underground again and travels through the Trout Brook Interceptor to the Mississippi River.

|

| This stop prompted many questions and observations about both the water’s route to and from the lake and the quality of the water as it leaves the lake. |

We are optimistic that our field trips were food for thought and will inspire students to come back to wonder and wander by the lakes again. When they return to school in the fall and have the opportunity to plant their rain gardens, we hope that they can make the connection between seeing these new additions on their school grounds and the memorable experiences they had while exploring their nearby lakes through new eyes.